This document is provided by the University of Iowa Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost and has been adapted from numerous faculty search publications. It is intended to serve as a referenced resource for faculty search committees to discuss faculty recruitment strategies in advance of beginning a search. It is designed to provide best practice strategies that support the university’s commitment to meeting its goals of enhancing excellence through faculty contributing to an inclusive culture. The document provides evidence-based strategies, with citation to the relevant research, to assist committee members in increasing their familiarity with the literature and to facilitate discussions at the departmental and collegiate levels. This document may be used in concert with search committee training, as a companion after reading selected articles or viewing a selected video, or as a tool for the committee chair to facilitate discussion as the committee begins its work. The Path to Distinction toolkit contains many of the evaluation tools and sample language described here to enhance the search process.

Faculty search committee members are also encouraged to review the Office of Institutional Equity (OIE) Recruitment Manual in advance of beginning a search to become familiar with the UI’s search process, equal employment opportunity/affirmative action (EEO/AA) guidelines and best practices. Relevant university policies can also be found in OIE’s online Recruitment Manual. OIE staff are available to provide consultations and resources to the hiring departments on EEO/AA requirements.

The Office of the Provost invites units to share their successful strategies so that they can be shared as tools and best practices with others on campus. Please send suggestions to faculty@uiowa.edu.

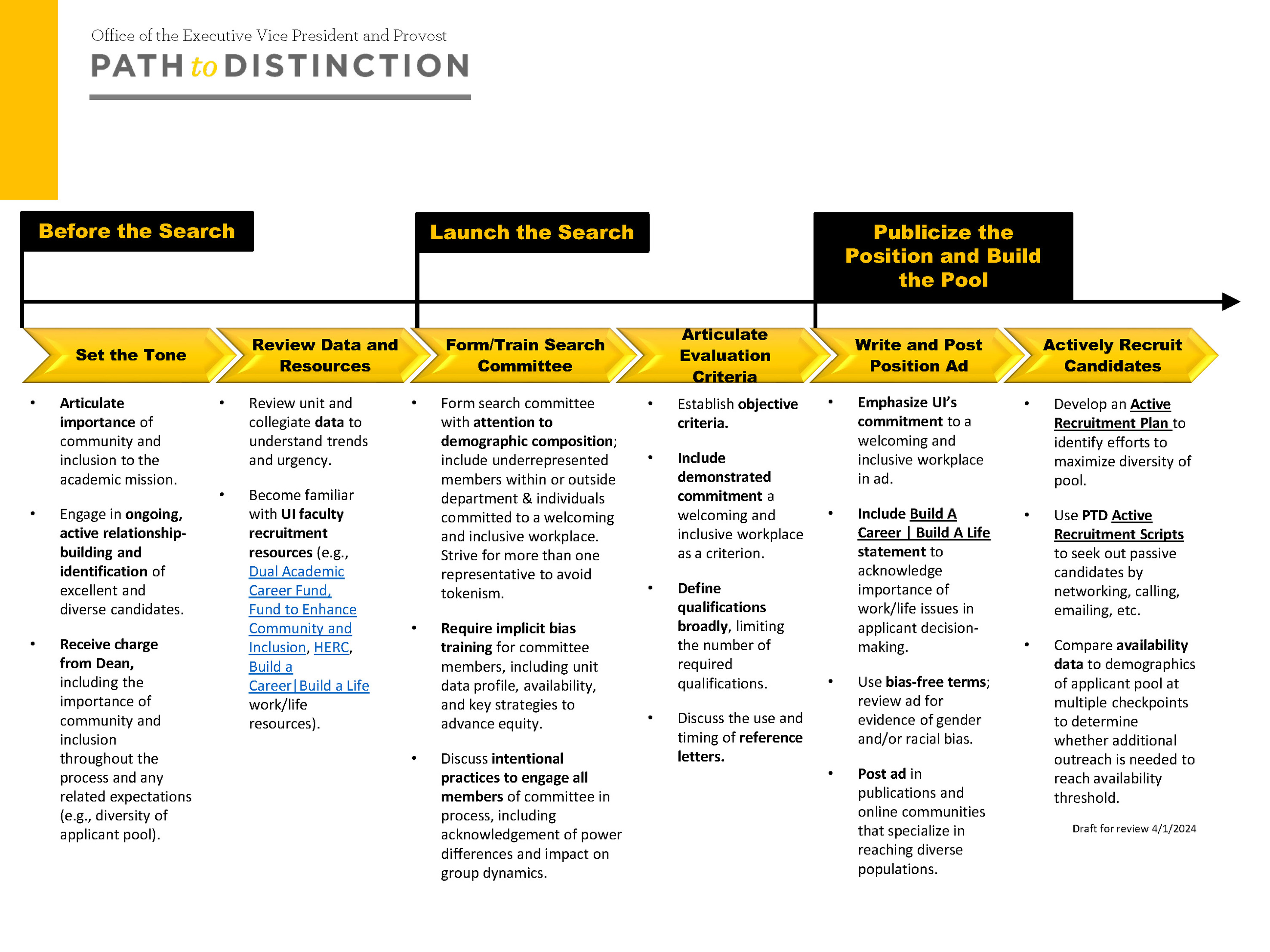

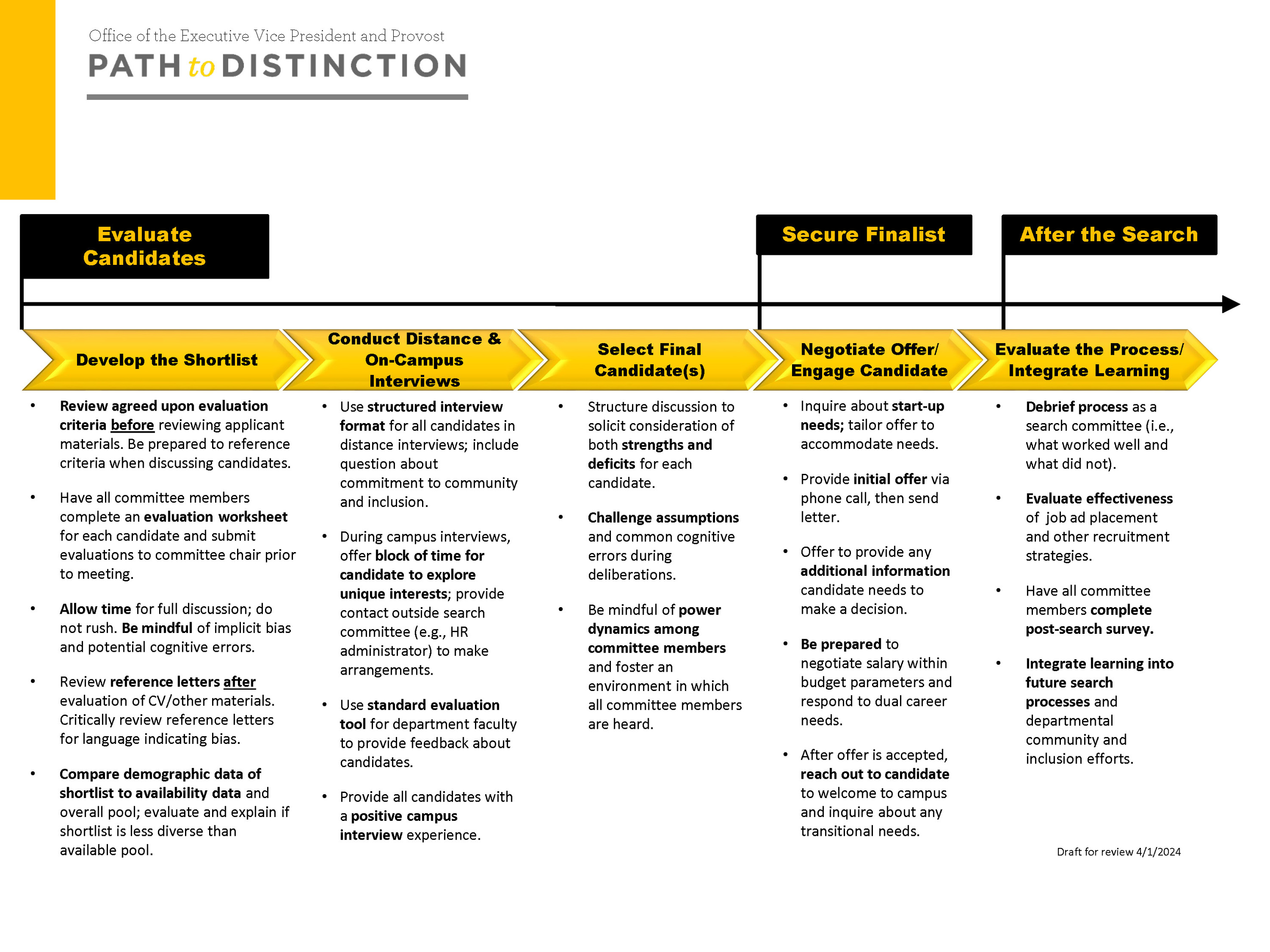

The faculty recruitment process is ongoing and starts before a department has permission to fill a specific faculty line. The University of Iowa faculty recruitment model shown above represents the various stages of a search process, beginning before the search with the college/department leadership setting the tone about the criticality of faculty who enhance community and inclusion. The model envisions several stages once a search is approved. At each stage, there are decision points and action steps. For example, during the Launch Search stage, the DEO will appoint a search committee and ensure that the members are properly prepared for their role, and the DEO will assist with articulating the evaluation criteria.

Research demonstrates that implicit bias has the potential to affect decisions at each stage. This manual provides strategies and practical tools that can reduce the impact of bias by standardizing processes, fully considering each candidate’s qualifications, and encouraging open communication among the committee members. This manual is organized according to the various search stages, with strategies and tools provided for each stage. The strategies are summarized in the search flow diagram below. Please review the relevant section for more detailed information and resources about particular strategies.

A recent review of search processes for faculty identified the following best practices:

- Training. All faculty search committees should have training at the outset of the search process, covering the following topics:

- implicit bias and how it can affect the faculty recruitment process

- tools and strategies to reduce the impact of bias, including those developed during the Path to Distinction project

- tools and methods for attracting a diverse applicant pool, including those developed during the Path to Distinction project

- EEO compliance topics

- Committee kick-off. Even if some search committee members have had similar training in the past, all search committee members should be expected to attend a search process overview/kick-off meeting at the beginning of the search process. This meeting can help to facilitate a shared understanding of the importance of inclusion and the specific efforts the committee will take to improve the process and outcomes.

- HR partner. A local Human Resources professional should partner with each faculty search committee to coordinate and track completion of training, and to coach the committee in implementing tools and best practices throughout the search process, including but not limited to tools from the Path to Distinction program, appropriate interview practices, and inclusion principles. The HR partner should not be a voting member of the committee; however, they should be an active partner to support and advise the committee throughout the search process including during committee deliberations.

- The HR partner should participate in the search committee training outlined above.

- The HR partner should also receive training about the faculty search process, Path to Distinction tools and resources, and strategies for working with faculty search committees.

- Diversity. When possible, faculty search committees should include members from diverse backgrounds using a broad definition, including various social identities such as gender, race/ethnicity, age, etc. as well as other factors such as academic rank, discipline or sub-discipline. Departments should be mindful of the burden placed on underrepresented faculty members who may be asked to provide a disproportionate share of service to the department and/or college. Committees may need to consider members from outside the hiring department and/or college to facilitate greater diversity among the committee, if there is also a connection to the search based on the individual’s academic/research expertise. Alternatively, faculty candidates should be interviewed by a broad representation of current faculty including individuals with diverse backgrounds.

- Feedback. Search committees should solicit feedback from those who participate in candidate interviews, using a standardized feedback instrument such as the tool available from the Path to Distinction project.

- Deans should articulate their full support for the importance of creating a welcoming and inclusive approach and procedures to enhance equitable treatment of candidates during the faculty search process. Deans are in the best position to set expectations related to faculty search procedures in their colleges and hold search committees accountable to those expectations.

This Toolkit and the Guidance document provide the basis for many of the recommendations noted above to enhance the faculty search process.

Set the Tone

- The department chair is the catalyst for change as it relates to developing a welcoming and inclusive workplace (1). The DEO plays a critical role in leading ongoing departmental dialogue to reinforce the importance of community and inclusion in achieving excellence.

- Explore questions similar to the following before beginning a search (2):

- Where do we want our department to be in 10 or 20 years?

- What new fields are emerging in this discipline?

- What perspectives and experiences are we missing?

- How will this position contribute to our goals of enhancing community and inclusion?

- Reimagine recruitment as an ongoing activity rather than as a one-time “post and pray” effort begun once a search has been authorized. Engage in ongoing scouting activities to “identify and build relationships with potential job candidates, so that the unit is in a good position to attract diverse pools of applicants for its approved searches” (3).

- Identify and periodically review specialized databases of underrepresented minority scholars and graduate students to identify potential scholars to invite to campus for invited talks.

- Big Ten Academic Alliance Doctoral Directory: btaa.org/students/doctoral-directory/the-doctoral-directory

- Central Midwest Higher Education Recruitment Consortium (HERC) resume/CV database: contact Adam Potter, adam-potter@uiowa.edu. (UI has an Institutional Membership, member.hercjobs.org/recruitment/jobs)

Review DEI Data & Resources

- Review department and/or collegiate demographic data and trends for student enrollment and faculty. Discuss trends and urgency of changing trends.

- Become familiar with UI diversity-related faculty recruitment resources including Build A Career | Build A Life, Path to Distinction tools and resources , HERC, Fund to Enhance Community and Inclusion, Dual Academic Career Fund, etc.

Form/Train Search Committee

- Increase the “bias literacy” of search committee members. “[I]mplicit bias is like a habit that can be broken through a combination of awareness of implicit bias, concern about the effects of that bias, and the application of strategies to reduce bias” (Devine, Forscher, Austin, & Cox, 2012, p. 1267). Intention, attention, and time are needed to learn new responses well enough to “compete with the formerly automatically activated responses” (Devine, 1989, p. 16).

- Encourage committee members to learn about the potential impact of implicit bias in search process. Schedule a committee training on implicit bias or recommend one of the following short videos and then discuss it during a search committee meeting:

- American Bar Association (n.d.). The neuroscience of implicit bias [Video, 21:11 min].

- Higher Education Recruitment Consortium (HERC) Webinars. Upcoming and archived webinars of interest to search committees are available at no charge to the UI community via the university’s institutional membership in the Central Midwest HERC. For more information: hercjobs.org/member_resources/Webinars/

- Kang, J. (2013). Immaculate perception: Jerry Kang at TEDxSanDiego 2013 [Video, 13:58 min].

- Ohio State University, The. (2012). The impact of implicit bias [Video, 5:33 min].

- UCLA Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (2016). Implicit bias video series [Seven-part video series], including “Lesson 6: Countermeasures.”

- Encourage committee members to take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) on Harvard University’s Project Implicit® website: implicit.harvard.edu/implicit. The site hosts 17 different IATs. Suggest committee members take similar tests (e.g., Gender-Career IAT, Weapons IAT) and discuss potential race/gender bias in the search process.

- Distribute and review this toolkit. Encourage individual members to take responsibility for consciously striving to minimize the influence of bias on their evaluation. Studies have shown that greater awareness of discrepancies between the ideals of impartiality and actual performance, together with strong internal motivations to respond without prejudice, can effectively reduce prejudicial behavior (4,5).

- Assemble a diverse committee with an expressed commitment to fostering community, inclusion and excellence (6). Studies show that the presence of people of color and women results in more careful and positive assessment of the evidence presented in candidates’ materials (6,7) and decreases discrimination against candidates (8). Additionally, research has shown that socially diverse groups are more innovative, incentivize group members to better prepare, encourage group members to anticipate alternative viewpoints and expect that reaching consensus will take effort (9).

- Schedule a presentation on implicit bias to increase committee members’ “bias literacy,” and explore evidence-based strategies for minimizing its influence; agree as a committee what strategies you will employ. Studies have shown that heightened awareness of the discrepancies between one’s ideals of impartiality and actual performance, together with strong internal motivations to respond without prejudice (“chronic egalitarianism”), can effectively reduce biased decision-making and behavior (5,10).

- Increase the committee’s sense of accountability for engaging in intentional, equitable processes. Encourage collegiate and/or departmental leadership to charge the committee to advance a welcoming and inclusive community and encourage committee members to avoid common cognitive errors that result in biased assessments.

- Discuss how committee member rank may affect committee deliberations and empower all committee members to ask questions to challenge assumptions and biases.

- Understand whether the charge of the committee is to provide an unranked list of the top three finalists or to rank order the committee’s preference. An unranked list may provide more flexibility to the final negotiator (e.g., Dean) and less stigma toward successful candidates who were not identified as the “top” choice.

- If multiple searches are taking place in your department, consider using a single search committee for all positions, to allow the consideration of a broader range of applicants.

Articulate Evaluation Criteria

- Broaden the job description to attract the widest possible range of qualified candidates. Limit “required qualifications” to identify true requirements of a position versus nice-to-haves. For example, studies show that female candidates are more likely to apply for positions when they meet 100% of the requirements while male candidates will apply when they meet only 60% (11).

- Establish objective criteria that will be used by all committee members. Disambiguate criteria as much as possible; when the basis for judgment is somewhat vague, biased judgments are more likely to occur (12,13).

- Scrutinize the criteria being used to ensure they are the correct criteria and don’t unintentionally screen out certain groups of candidates or outcomes (14).

- Include “demonstrated commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion” or similar requirement as an evaluation criterion.

- Consider requiring a “commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion statement” as part of candidates’ application materials. See Path to Distinction Toolkit for more information, including examples of evaluation grids and guidance for applicants and search committees.

- Discuss the use and timing of reference letters. Be aware that reference letters may reflect implicit bias and/or contain gendered terminology. In addition, relying on the prestige of the referee may negatively impact underrepresented candidates. If possible, do not review reference letters until later in the selection process after the search committee has conducted its own evaluation of the candidates.

- Use a reference prompt when requesting letters of reference to guide the letter writer to address specific qualifications of the candidates.

Write and Post Ad

- Emphasize the university’s and the college or department’s commitment to excellence and inclusion.

- Include Build A Career | Build A Life link and statement to acknowledge the importance of dual career and work life issues in applicant decision-making. Use language that signals a commitment to dual-career couples and work/life balance. For more information about local work/life resources, including dual-career support, please see: worklife.uiowa.edu.

- Use bias-free terms; screen the position ad for stereotype-priming language (15). Use tools such as the Gender Bias Calculator or the Gender Decoder to detect gendered terminology.

- To ensure compliance with federal regulations, the UI Office of Institutional Equity requires the tagline stated in the Policy Manual §III-9.6(b)(3) in all [external] ads. See the OIE Recruitment Manual for more information.

- Consider the following questions when writing the job ad:

- What qualifications must the person have to succeed in this role?

- What qualifications might enhance their success and impact?

- Are there people who could succeed in this role but who wouldn’t meet our qualifications?

- Are we reflecting a range of interests, backgrounds, and experiences in our description of the position, unit, and institution? Have we described the position’s role, its impact, and how it contributes to fostering community and inclusion?

Actively Recruit Applicants

- Reach out to applicants from underrepresented groups individually before and during a search. For example, seek out talented scholars at conferences and invite them to campus to present their research. Consider preparing student recruiters to discuss employment opportunities with peers and/or faculty mentors when attending conferences and other events designed for underrepresented students.

- Consider data about the availability of underrepresented candidates in your field. For example:

- NSF Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED) is an annual census conducted since 1957 of all individuals receiving a research doctorate from an accredited U.S. institution in a given academic year, available for specific disciplines: nsf.gov/statistics/srvydoctorates/

- Obtain demographic data for the applicant pool (for pools of 15 or more) from the Office of Institutional Equity and compare to availability data. Consider additional outreach methods to further diversify the pool.

- Develop an Active Recruitment Plan to maximize the potential of developing a diverse applicant pool, using tools found in the toolkit. Do NOT rely on the “post and pray” method to attract a diverse candidate pool.

- Use Active Recruitment Scripts to seek out passive candidates through networking, requesting referrals, calling and emailing high potential underrepresented scholars.. When contacting colleagues for referrals, specifically ask that they consider underrepresented scholars in their referrals.

- Actively search for candidates using jobseeker databases and services designed to attract diverse applicant pools. The University of Iowa has access to the Higher Education Recruitment Consortium (HERC) jobseeker database and the Big Ten Academic Alliance Directory of URM postdoc STEM scholars at Big Ten universities. For more information about how to access these resources, contact the Office of the Provost: faculty@uiowa.edu.

- Pay attention to expectancy bias based on institutional reputation and consider reaching out to candidates who may be currently under-placed and thriving at less well-ranked institutions.

Develop the Shortlist

- Review agreed upon evaluation criteria before reviewing applicant materials; apply criteria consistently to all applicants. Be prepared to reference criteria when discussing candidates. When criteria are not clearly articulated before reviewing candidates, evaluators may shift or emphasize criteria that favor candidates from well-represented demographic groups (5,12,16).

- Have all committee members complete an evaluation worksheet for each candidate and submit evaluations to committee chair prior to meeting. Using an evaluation rubric when reviewing CVs/résumés encourages objective justifications before discussions at search committee meetings.

- Allow sufficient time to evaluate and discuss each applicant. Be mindful of implicit bias and potential cognitive errors. Reduce time pressure and cognitive distraction when evaluating applications. Evaluators who were busy, distracted by other tasks, and under time pressure gave women lower ratings than men for the same written evaluation of job performance. Bias decreased when they were able to give adequate time (approximately 15-20 minutes per candidate) and attention to their judgments (5,17,18).

- Review reference letters after evaluation of CV/other materials. Critically review reference letters for language indicating bias (e.g., gender, race). Use the Gender Bias Calculator or the Gender Decoder tool to identify potential gendered terminology.

- Compare demographic data of shortlist to availability data and overall pool; evaluate and explain if shortlist is less diverse than available pool.

- When possible, implement blinded review, evaluation, and grading processes (19,20).

- Be able to defend every decision for eliminating or advancing a candidate. Research shows that holding evaluators to high standards of accountability for the fairness of their evaluation reduces the influence of bias and assumptions (21).

- Use an inclusion strategy rather than exclusion strategy when evaluating CVs. An inclusion strategy identifies which candidates are suitable for consideration; whereas an exclusion strategy decides which should be eliminated. Studies show that exclusion strategies result in higher levels of criterion stereotyping (i.e., setting different decision thresholds for judging members of different groups), sensitivity stereotyping (i.e., greater difficulty distinguishing among members of stereotyped groups), and larger sets of ultimately excluded candidates due to inclusion-exclusion discrepancy (22,23).

- Evaluate each candidate’s entire application; don’t depend too heavily on only one element (e.g., focus too heavily on letters of recommendation, prestige of the degree-granting institution, teaching evaluations, excellent communication skills). Studies show significant patterns of difference in letters of recommendation for male and female applicants (24,25), and differences in student evaluations for women, gay men, and faculty of color (26-28).

- If a diversity statement was requested of applicants, create evaluation criteria for assessing its strength before reviewing the submissions.

- Periodically evaluate your judgments, determine whether qualified women and underrepresented minorities are included in your pool, and consider whether evaluation biases and assumptions are influencing your decisions. Assign someone to remind the committee members to reflect on the following questions:

- Are women and minority candidates subject to different expectations or standards in order to be considered as qualified as majority men?

- Are candidates from institutions other than the major research universities that have trained most of our faculty being under-valued?

- Have the accomplishments, ideas, and findings of women or minority candidates been undervalued or unfairly attributed to a research director or collaborators despite contrary evidence in publications or letters of reference?

- Is the ability of women or minorities to run a research group, raise funds, and supervise students and staff of different gender or ethnicity being underestimated?

- Are assumptions about possible family responsibilities and their effect on a candidate’s career path negatively influencing evaluation of a candidate’s merit, despite evidence of productivity?

- Are negative assumptions about whether women or minority candidates will ‘fit in’ to the existing environment influencing evaluation?

- After the initial review of candidates, reflect on the following questions:

- What facts support our decisions to include or exclude a candidate? Where might we be speculating?

- How do the demographics of our shortlist compare with our qualified pool, and with the national pool of recent Ph.Ds.?

- Have we generated an interview list with more than one minority finalist?

- If a high percentage of underrepresented candidates were weeded out, do we know why? Can we reconsider our pool with a more inclusive lens, or extend the search?

Conduct Distance and On-Campus Interviews

- Use a structured interview format for all candidates in distance interviews.

- Include questions about commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion during distance interviews and on-campus interviews. Pay attention to which member of the Search Committee asks the question (e.g., avoid having the only underrepresented minority committee member always ask the “diversity” question).

- Ask all interview candidates where they learned about the position opening to determine what sources provided the most promising candidates.

- During campus interviews, offer a block of time (e.g., two hours) for candidates to explore unique interests; provide a contact outside search committee (e.g., HR administrator) to make arrangements. The UI Work/Life Resources website can be used as a menu of options to encourage candidates to consider how they might wish to use the time. For example, a candidate may want to talk with someone about local faith communities or someone from a specific group (e.g., African American, LGBT) about what it is like to live/work here.

- Use a standard evaluation tool for department faculty to provide feedback about candidates.

- Provide all candidates with a positive campus interview experience. Create a process and atmosphere that welcomes candidates. Every candidate should leave the University of Iowa with positive regard for the institution, whether or not they are the finalist. Communicate the welcome in pre-interview communication, in preparation for on-campus interviews, in communications with applicants who were not selected for interviews and/or offers.

- Develop a welcome packet that includes information about UI’s strengths as an environment in which employees can thrive. Include the “Build a Career | Build a Life at the University of Iowa” flyer in interviewee packets and/or online correspondence to inform candidates of UI’s Work/Life and Dual-Career Resources.

- Use a standard protocol for each campus visit to ensure a consistent review process for each candidate. Develop interview questions in advance of the interview and be as consistent as possible for all candidates (e.g., same person assigned to each question, interviews conducted in a consistent setting, same time allotment). For more information, including tips for interviewing candidates with disabilities, see the Office of Institutional Equity’s the Selection Process.

- Pay attention to the climate of the interview process, including nonverbal and verbal communication. (29,30). Become familiar with common patterns of micro-messages in formal and informal conversations that may convey bias. Examples include: mispronunciation of names, “othering” comments (e.g., “That’s an interesting accent.”), stereotypical assumptions such as “Why would you be interested in a position at Iowa?” (31-33).

Select Finalists

- Structure discussion to solicit consideration of both strengths and deficits for each candidate.

- Challenge assumptions and common cognitive errors during deliberations.

- Be mindful of power dynamics among committee members and foster an environment in which all committee members are heard.

This stage will be facilitated by the DEO and/or Dean’s Office, not the search committee.

Negotiate Offer/Engage Candidate

- Inquire about start-up needs; tailor the offer to accommodate needs.

- Provide initial offer via phone call, then send a letter.

- Offer to provide any additional information the candidate needs to make a decision.

- Be prepared to negotiate salary within budget parameters and respond to dual career needs.

- After the offer is accepted, reach out to the candidate to welcome them to campus and inquire about any transitional needs.

Evaluate the Process/Integrate Learning

- Debrief the process and outcomes achieved as a search committee (i.e., what worked well and what did not). What would the committee recommend for future searches?

- Evaluate effectiveness of job ad placement and other recruitment strategies, based on the recruitment sources that attracted the candidates selected for interview.

- Have all committee members complete a post-search survey.

- Integrate learning into future search processes and departmental community building efforts.

- Consider the following points:

- Recruiting Resources: Compare resources used with the recruiting resources applicants reported utilizing

- Applicant Pool: Number of applicants, demographics of applicant pool (self-reported)

- Interview Candidates: Number of candidates interviewed and demographics

- Committee Process: Composition, processes that worked well (e.g., interview schedule), processes that members might change next time

- Offer(s) Made: Number and demographics (DEO will have this information)

- Offer Accepted: Demographics (DEO will have this information)

References

- Chun, E and Evans A. (2015) The Department Chair as Transformative Diversity Leaders: Building inclusive learning environments in higher education Stylus Pub LLC

- Gilies, A. (2016). Questions to ask to help create a diverse applicant pool. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com/article/Questions-to-Ask-to-Help/237747?cid=rc_right

- University of Washington. (2016). Best practices for faculty searches. Retrieved from http://www.washington.edu/diversity/faculty-advancement/handbook/

- Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. L. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1267-1278. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003

Fine, E., & Handelsman, J. (2010). Benefits and challenges of diversity in academic settings. Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-WISELI website: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/Benefits_Challenges.pdf

Fine, E., & Handelsman, J. (2012a). Reviewing applicants: Research on bias and assumptions. Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-WISELI website: http://wiseli.engr.wisc.edu/docs/BiasBrochure_3rdEd.pdf

Fine, E., & Handelsman, J. (2012b). Searching for excellence & diversity®: A guide for search committee members. Retrieved from University of Wisconsin-WISELI website: https://wiseli.wisc.edu/resources/guidebooks-brochures/

- Kang, J., Bennett, M., Carbado, D., Casey, P., Dasgupta, N., Faignman, D., Godsil, R.D., Greenwald, A.G., Levinson, J.D., & Mnookin, J. (2012). Implicit bias in the courtroom. UCLA Law Review, 59(1124).

- Sommers, S. (2006). On racial diversity and group decision making: Identifying multiple effects of racial composition on jury deliberation. Journal of Personality Social Psychology, 90(4), 597-612.

- Heilman, M. E. (1980). The impact of situational factors on personnel decisions concerning women: Varying the sex composition of the applicant pool. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 26, 386-395.

- Phillips, K.W. (2014). How diversity makes us smarter. Scientific American, 311(4). Retrieved from scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter/.

- Carnes, M., Devine, P. G., Manwell, L., Byars-Winston, A., Fine, E., Ford, C. E., Forscher, P., Issaac, C., Kaatz, A., Magua, W., Palta, M., & Sheridan, J. (2015). The effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: A cluster randomized, controlled trial. Academic Medicine, 90(2), 221-230. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000552

- Desvaux, G., Devillard-Hoellinger, S., & Meaney, M. C. (2008). A business case for women.

- Biernat, M., & Fuegen, K. (2001). Shifting standards and the evaluation of competence: Complexity in gender-based judgment and decision making. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 707-724. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00237

- Casey, P. M., Warren, P. K., Cheesman, II, & Elek, J. J. (2012). Helping courts address implicit bias: Resources for education. Retrieved from http://www.ncsc.org/ibeducation

- Correll, S.J., (2015). Creating a level playing field: Discussion guide. Retrieved from https://stanford.app.box.com/s/xt0voqfemn4z6kyxym6ymz2uejfkzuo7

- Leibbrandt, A., & List, J. A. (2012). Do women avoid salary negotiations? Evidence from a scale natural field experiment. NBER Working Paper Series. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w18511

- Uhlmann, E. L., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). "I think it, therefore it’s true”: Effects of self-perceived objectivity on hiring discrimination. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 104, 207-223.

- Martell, R. F. (1991). Sex bias at work: The effects of attentional and memory demands on performance ratings of men and women. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21(23), 1939-1960. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1991.tb00515.x

- Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2002). Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration web site. Group Dynamics Theory Research and Practice, 6(1), 101-115.

- Goldin, C., & Rouse, C. (2000). Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of “blind” auditions on female musicians. American Economic Review, 90(4), 715-741.

- Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2013). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. New York, NY: New Delacorte Press.

- Foschi, M. (1996). Double standards in the evaluation of men and women. Social Psychology Quarterly, 59, 237-254.

- Hugenberg, K., Bodenhausen, G. V., & McLain, M. (2006). Framing discrimination: Effects of inclusion versus exclusion mind-sets on stereotypic judgments. 91(6), 1020-1031.

- Yaniv, I., & Schul, Y. (2000). Acceptance and elimination procedures in choice: Noncomplimentarity and the role of implied status quo. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(2), 293-313. doi:10.1006/obhd.2000.2899

- 24. Madera, J. M., Hebl, M. R., & Martin, R. C. (2009). Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: Agentic and communal differences. 94, 6, 1591-1599.

- Trix, F., & Psenka, C. (2003). Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse and Society, 14(2), 191-220.

- Uhlmann, E. L., & Cohen, G. L. (2005). Constructed criteria: Redefining merit to justify discrimination. Psychological Science, 16(6), 474-480.

- MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A. N. (2015). What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of 24. Madera, J. M., Hebl, M. R., & Martin, R. C. (2009). Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: Agentic and communal differences. 94, 6, 1591-1599.

- Schmidt, B. (2015). Gendered language in teacher reviews. Retrieved from http://benschmidt.org/profGender/#

- Falkoff, M. (2018, April 25). Why We Must Stop Relying on Student Ratings of Teaching. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Why-We-Must-Stop-Relying-on/243213

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2000). Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science, 11(4), 315-319.

- Elliott, A. M., Alexander, S. C., Mescher, C. A., Mohan, D., & Barnato, A. E. (2016). Differences in physicians’ verbal and nonverbal communication with Black and White patients at the end of life. 3924, 1-8.

- Morrell, C., & Parker, C. (2013). Adjusting micromessages to improve equity in STEM. Diversity & Democracy, 16(2). 26-27.

- Rowe, M. P. (1990). Barriers to equality: The power of subtle discrimination to maintain unequal opportunity. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 3(2), 153-163. doi:10.1007/bf01388340

- Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5-18.

- Madera JM, Hebl MR, Dial H, Martin R, Valian V. (2019) Raising doubt in letters of recommendation for academia: gender differences and their impact. J. Business Psychol. 34:287-303.

- Schmader T, Whitehead J, Wysocki V. (2007) A linguistic comparison of letters of recommendation for male and female chemistry and biochemistry job applicants. Sex Roles 57:509-514.

- Dutt K, Pfaff D, Bernstein A, Dillard J, Block C. (2016) Gender differences in recommendation letters for postdoctoral fellowships in geoscience. Nature Geoscience, 9(11), 805-808.

Additional References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Baker, R., Dee., T., Evans, T., & John, J. (2018). Bias in online classes: Evidence from a field experiment (CEPA Working Paper No.18-03). Retrieved from Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis: http://cepa.stanford.edu/wp18- 03

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. The American Economic Review, 94(4), 991-1013.

Biernat, M., Manis, M., & Nelson, T. E. (1991). Stereotypes and standards of judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 485-499.

Blair, I. V., & Banaji, M. R. (1996). Automatic and controlled processes in stereotype priming. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1142-1163.

Carnes, M. (Producer). Implicit stereotype-based bias: Potential impact on faculty career development. Retrieved from the American Council on Education website: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/2-Carnes.PDF

Chambers, D. W. (1983). Stereotypic images of the scientist: The Draw-a-Scientist Test. Science Education Assessment Instruments, 67(2), 255-265.

Chaney, J., Burke, A., & Burkley, E. (2011). Do American Indian mascots = American Indian people? Examining implicit bias towards American Indian people and American Indian mascots. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center, 18(1), 42-62.

Clark, P., & Zygmunt, E. (2014). A close encounter with personal bias: Pedagogical implications for teacher education. The Journal of Negro Education, 83(2), 147-161.

Cooper, S. (2016). Nine non-threatening leadership strategies for women. Retrieved from http://qz.com/745032/nine-non-threatening-leadership-strategies-for-women/

Correll, S.J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297-1339.

Correll, S.J., & Simard, C. (2016, April 29). Research: Vague feedback is holding women back. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2016/04/research-vague-feedback-is-holding-women-back

Dixon, T. L., & Linz, D. (2000). Overrepresentation and underrepresentation of African Americans and Latinos as lawbreakers on television news. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 131-154.

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2000). Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science, 11(4), 315-319.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573-598.

Green, A. R., Carney, D. R., Pallin, D. J., Ngo, L. H., Raymond, K. L., Iezzoni, L. I., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and White patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(9), 1231-1238.

Gündemir, S., Homan, A. C., de Dreu, C. K. W., & van Vugt, M. (2014). Think leader, think White? Capturing and weakening an implicit pro-White leadership bias. PLOS ONE, 9(1), 1-10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083915

Heilman, M. E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women's ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 657-674.

Heilman, M. E., Wallen, A. S., Fuchs, D., & Tamkins, M. M. (2004). Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 416-427.

Hurtado, S., & DeAngelo, L. (2009). Keeping senior women at your college. Retrieved from http://www.aaup.org/AAUP/pubsres/academe/2009/SO/Feat/Hurt.htm

Hurtado, S., & Figueroa, T. (2013). Women of color faculty in science technology engineering and mathematics: Experiences in academia. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association (AERA), San Francisco, California. http://www.heri.ucla.edu/nih/downloads/AERA-2013-WOC-STEM.pdf

Jackson, J. F. L. (2008). Race segregation across the academic workforce: Exploring factors that may contribute to the disparate representation of African American men. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(7).

Jaschik, S., & Lederman, D. (2017). 2017 survey of college and university presidents. Retrieved from http://www.insidehighered.com

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Kang, J., Bennett, M., Carbado, D., Casey, P., Dasgupta, N., Faignman, D., Godsil, R.D., Greenwald, A.G., Levinson, J.D., & Mnookin, J. (2012). Implicit bias in the courtroom. UCLA Law Review, 59(1124).

Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, Ohio State University . Implicit bias module series. https://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/implicit-bias-module-series

Lebrecht, S., Pierce, L. J., Tarr, M. J., & Tanaka, J. W. (2009). Perceptual other-race training reduces implicit racial bias. PLOS ONE, 4(1). doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0004215.

Livingston, R. W. (2013). Gender, race, and leadership: An examination of the challenges facing non-prototypical leaders. Presentation at W50 Research Symposium. Harvard Business School Video. Retrieved from https://universitywebinars.org/gender-race-and-leadership-an-examination-of-the-challenges-facing-non- prototypical-leaders-from-robert-livingston-at-harvard/.

Mekawi, Y. & Bresin, K. (2015). Is the evidence from racial bias shooting task studies a smoking gun? Results from a meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 61, 120-130. 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.08.002.

Milkman, K. L., Akinola, M., & Chugh, D. (2014). What happens before? A field experiment exploring how pay and representation differentially shape bias on the pathway into organizations. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2063742

Miller, C. C. (2017, January 16). Job listings that are too ‘feminine’ for men. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/16/upshot/job-disconnect-male-applicants-feminine-language.html

Miller, C. C. (2016). Is blind hiring the best hiring? Retrieved from The New York Times Magazine website: http://nyti.ms/20WFZqF

Moody, J. A. (2007). Rising above cognitive errors: Guidelines for search, tenure review, and other evaluation committees. Retrieved from http://www.ccas.net/files/ADVANCE/Moody%20Rising%20above%20Cognitive%20Errors%20List.pdf.

Moss-Racusin, C. A. (2014). Scientific diversity interventions. Science, 343, 615-616. doi:10.1126/science1245936

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. PNAS, 109(41), 16474-16479.

Norton, M. I. (2013). The costs of racial color blindness [Video, 4:49]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RG6cVIDneis

Peck, E. (2015). Here are the words that may keep women from applying for jobs. Retrieved from Huffington Post website: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/02/textio-unitive-bias-software_n_7493624.html

Phelps, E. A., Connor, K. J., Cunningham, W. A., Funayama, E. S., Gatenby, J. C., Gore, J. C., & Banaji, M. R. (2000). Performance on indirect measures of race evaluation predicts amygdala activation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12(5), 729-738. doi:10.1162/089892900562552

Pittman, C. (2010). Race and gender oppression in the classroom: The experiences of women faculty of color with White male students. Teaching Sociology, 38(3), 183-196. doi:10.1177/0092055X10370120

Pittman, C. (2012). Racial microaggressions: The narratives of African American faculty at a predominantly White university. Journal of Negro Education, 81(1), 82-92.

Quillian, L., Pager, D., Midtbøen, A.H., & Hexel, O. (2017). Hiring discrimination against Black Americans hasn’t declined in 25 years. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/10/hiring-discrimination-against-black-americans-hasnt-declined-in-25-years

Rachlinski, J. J., Guthrie, C., & Wistrich, A. J. (2006). Inside the bankruptcy judge's mind. Boston University Law Review, 86, 1227.

Rachlinski, J. J., Johnson, S. L., Wistrich, A. J., & Guthrie, C. (2009). Does unconscious racial bias affect trial judges? Notre Dame Law Review, 84(3).

Ridgeway, C. L. (2001). Gender, status, and leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 637-655.

Rosette, A. S., Koval, C. A., May, A., & Livingston, R. (2016). Race matters for women leaders: Intersectional effects on agentic deficiencies and penalties. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 429-445.

Rowe, M. (1974). Saturn's rings: A study of minutiae of sexism which maintain discrimination and inhibit affirmative action results and non-profit institutions. Graduate and Professional Education of Women, 1-9.

Rowe, M. (2008). Micro-affirmations and micro-inequities. The Journal of the International Ombudsman Association, 1(1).

Russ, T. L., Simonds, C. J., & Hunt, S. K. (2002). Coming out in the classroom…An occupational hazard?: The influence of sexual orientation on teacher credibility and perceived student learning. Communication Education, 51(3), 311- 324.

Smith, D. G. (2000). How to diversify the faculty. Academe, 86(5), 48-52. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40251921

Smith, F. L., Tabak, F., Showail, S., Parks, J. M., & Kleist, J. S. (2005). The name game: Employability evaluations of prototypical applicants with stereotypical feminine and masculine first names. Sex Roles, 52(1), 63-82.

Steele, C. M. (2010). Whistling Vivaldi: How stereotypes affect us and what we can do. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797-811.

Steinpreis, R., Anders, K. A., & Ritzke, D. (1999). The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study. Sex Roles, 41(7), 509-528.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271-286. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

Sullivan, J. (2015). How to reduce hiring bias against women. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/experts/2015/10/27/how-to-reduce-hiring-bias-against-women/

Sy, T., Shore, L. M., Shore, T. H., Tram, S., Strauss, J., Whiteley, P., & Ikeda-Muromachi, K. (2010). Leadership perceptions as a function of race-occupation fit: The case of Asian Americans. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 902-919.

Thomas, K. M., Johnson-Bailey, J., Phelps, R. E., Tran, N. M., & Johnson, L. N. (2009). Women of color at midcareer: Going from pet to threat. In L. Comaz-Dias & B. Greene (Eds.), Psychological health of women of color: Intersections challenges and opportunities (pp. 275-286). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Tilcsik, A. (2011). Pride and prejudice: Employment discrimination against openly gay men in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 117(2), 586-626. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/661653

Todd, A. R., Thiem, K. C., & Neel, R. (2016). Does seeing faces of young black boys facilitate the identification of threatening stimuli? Psychological Science, 1-10. doi:10.1177/0956797615624492

Utt, J. (2015). 10 ways well-meaning White teachers bring racism into our schools. Retrieved from http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/08/10-ways-well-meaning-white-teachers-bring-racism-into-our-schools

Utz, R. (2017, January 18). The diversity question and the administrative-job interview. Retrieved from The Chronicle of Higher Education: http://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Diversity Question the/238914

Valian, V. (1999). Why so slow? The advancement of women. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Valian, V. (2005). Beyond gender schemas: Improving the advancement of women in academia. Hypatia, 20(3), 198-213. van Ommeren, J., de Vries, R. E., Russo, G., & van Ommeren, M. (2005). Context in selection of men and women in hiring decisions: Gender composition of the applicant pool. Psychological Reports, 96(2), 349-360.

Vendantam, S. (2014) Evidence of racial, gender biases found in mentoring/Interviewer: National Public Radio. Wennerås, C., & Wold, A. (1997). Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature, 387, 341-343.

Yaniv, I., & Schul, Y. (1997). Elimination and inclusion procedures. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 10, 211-220.

Educational Videos and Activities for Search Committee Members

American Bar Association. (n.d.). The neuroscience of implicit bias. Retrieved from http://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/initiatives/task-force-implicit-bias.html

Association of American Medical Colleges. (n.d.). What you don't know: The science of unconscious bias and what to do about it in the search and recruitment process [Online video tutorial]. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/members/leadership/catalog/178420/unconscious_bias.html

Higher Education Recruitment Consortium (HERC) Webinars. Upcoming and archived webinars of interest to search committees are available at no charge to the UI community via the university’s institutional membership in the Central Midwest HERC. For more information: https://www.hercjobs.org/member_resources/Webinars/

Kang, J. (2013). Immaculate perception: Jerry Kang at TEDxSanDiego 2013 [Video, 13:58 min]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VGbwNI6Ssk

Ohio State University. (2012). The impact of implicit bias [Video, 5:33 min]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/UZHxFU7TYo4

Project Implicit® - Harvard University. (n.d.). Implicit Association Test. Retrieved from https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

UCLA Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (2016). Implicit bias video series [Seven-part video series].